Joe Sutter had a problem.

It wouldn’t be his first. Or his last on this project, the development of the Boeing 747.

This particular problem was monumental. Namely, how could he and the team make a fuselage on a brand new airplane spacious enough to carry a large amount of passengers and big enough to transport a large amount of freight?

Every solution to date involved thinking of the plane’s body like two long shipping containers. Lay one container on the bottom for cargo and stack another one on top for people.

This stacked, “double-decker”solution, born from the sea and the way a ship would meet the challenge, wasn’t going to fly.

You see, at Boeing, it’s safety first. And the passengers on top of this stacked solution could not escape in under 90 seconds in the event of an emergency, (The FAA standard.)

What’s more, this double-decker solve couldn’t solve the additional demands for cargo space and equipment space in this configuration. More problems, more solutions required…more headaches.

So Joe Sutter, head of the 747 development team, had a big problem.

Until he didn’t.

Until someone on the team, “…transformed Mr. Sutter’s napkin doodles into the humpbacked, wide-bodied behemoth passenger and cargo plane known as the 747…” (As The New York Times put it.)

These doodles of the 747, sometimes referred to as “two boxes in a circle” or simply the “wide oval” would change the world and the way the world would experience flight.

These doodle-diagrams would often take the form of a cross-section look at the plane: imagine the 747, head-on, as a wide egg-shaped oval.

Not two stacked containers, one on top of another.

But one wide section. With the “double-decker” sections put, side-by-side, in effect.

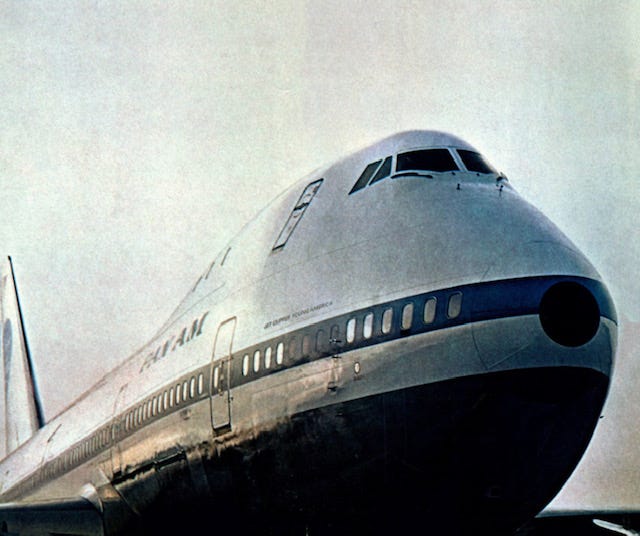

In this form, Boeing would create the first “wide body” airplane.

A plane with two aisles instead of one.

A plane that was twice the size of the conventional planes at the time, the Boeing 707 and the DC-8.

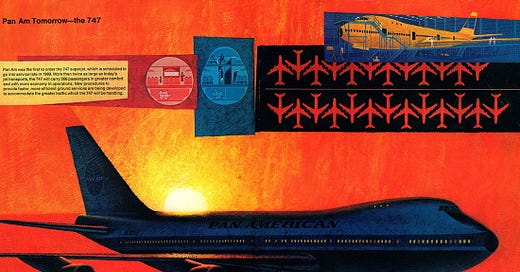

And a plane with an iconic flight deck on top that would appear as a hump.

This was something no one had ever seen before, but the engineering data showed a solution that was undeniable.

Now all Boeing had to do was sell it to their key customer, Juan Trippe, the legendary and charismatic founder of Pan Am Airways.

The pitch meeting had the same creative spirit as the plane itself.

The story goes that the Boeing team brought a rope with a knot or two that marked off the dimensions of the 747’s cabin.

When the team prepped the room for the meeting in the iconic PanAm building, they measured the room space using the rope. And to their delight between the width and the ceiling, the room was miraculously, roughly, the same size as the 747 cabin.

So when they leveled the boom that PanAm wasn’t going to get a double-decker, but instead, “a wide body” they could turn Trippe’s frown upside down and literally blow him away with the size of the plane.

This was experiential selling, and indeed, Trippe was amazed.

He also was intrigued by the 747’s iconic hump.

The Boeing team bursted with pride over the advanced cockpit for the pilots and the hump space behind it which would be perfect as a resting space for the crew.

But Juan Trippe was feeding off the creativity of the moment and instead decided that the space would be even better served as the world’s first cocktail lounge in the sky.

There is so much to learn studying the development of the 747.

Innovation. Visioneering. System Design. Aeronautics. Avionics. Resilience. Lateral Thinking. Logistics. Interior Design. Manufacturing. Labor Relations. Project Management. Finance. Marketing. PR.

For now here are five lessons you can use.

1\ You need a Vision

The 747 set out to be the best multi-use airplane ever. For you and your projects, you need a clear view of what you’re trying to accomplish. It can be a small vision. Or it can be a gigantic vision like the 747. The point is, have one.

2\ Conventional thinking can only take you so far

As much as everyone believed (and Juan Trippe wanted) a “double-decker” solution, it ultimately was not the best solution. Which lead the team to take a leap and find something better.

3\ Reduction

There was a lot of engineering and jargon concerning the 747 challenges, but ultimately the solution could be explained simply, often in a drawing. For you, think about breaking down your problem and your solution into its elements. What’s the simplest way to describe what you’re trying to do? What’s the simplest way to explain it? What’s the simplest way to show it?

4\ Make the selling of your idea as creative as the idea itself

When the Boeing team discovered the presentation room was the same size as a section of the 747, they realized their customer could actually experience the product. This would be way more compelling than any slide show.

5\ Be open to the unexpected

Juan Trippe was expecting a double-decker. Instead he got a a two-aisle wide body. Give Trippe credit for abandoning what he thought he wanted coming into the room. And accepting the better idea. (No small feat when you consider he was going to pay millions for each 747 he bought — and he bought a lot.)

Also, give the Boeing team credit. They had one idea for the hump space — a crew rest area — but they were open to Trippe’s idea of a swanky lounge.

All of this comes to the fore as just this past week, Boeing built and delivered the last 747.

It marks the end of an era.

But the stories, the ways of thinking, and the lessons, well, they can still help you and your ideas take flight.

My father worked in the Pan Am building from it's opening until 1978.

I guess that when airlines were still run by flyers.

Because Frank Borman ran Eastern.